Chasing Darkness in Coonabarabran

Chasing Darkness in Coonabarabran

The morning is crisp and I still haven’t made any friends after yesterday’s brush with darkness, and dark moods. I delicately approach the four blokes discussing last night’s perfection.

“Is darkness genuinely quantifiable or is it just an absence of light?”

My carefully worded question does not cause immediate laughter. When they launch into some in-depth and fascinating explanations, I catch the motel lady, Sally, quietly giggling under the awning.

Late the day before I’d arrived in Coonabarabran, NSW and noticed a man hurriedly packing a tripod into his car. He was slightly agitated when I approached to ask directions to the Dark Sky Park I’d come to see - the only one in Australia, and indeed the whole southern hemisphere. A place where the night sky is so untroubled by artificial light that you can see the stars as clearly as possible with a puny human eye. My excitement and awe carried no truck with the hurrying stranger.

“You won’t get much here tonight, mate,” he snapped, casting a briefly envious eye in the direction of my sleek Mazda BT-50 SP. “There’s a cloudy haze forecast. A lot clearer in Narrabri. There’s an open day at the observatory there. There’s a few of us going”. With that he was off.

I didn’t drive more than six hours to not experience the famed dark sky, so I took his advice and rushed north in search of clear darkness, and what’s described as one of the best night sky viewing areas in the country. As a photographer, I had big plans to catch incredible images of both my Mazda and the universe, and cloud was not part of my plans.

The sun had gone when I finally made it to the boom gate of the observatory, which magically raised in front of me. As soon as I drove into the carpark I was assailed by a snappy and unhappy man. “How did YOU get in? Have you BOOKED? No? LEAVE please, see you later.”

He said all this in a terrific rush with no punctuating. I saw people with tripods and telescopes lined up beside the two large dishes pointed skyward and I thought I might start explaining, or begging, but I could see he was in no mood. I left, quietly cursing, in search of my own chunk of darkness. Fortunately there’s plenty of it around these parts.

And it was actually fortunate for me that he made me leave. I had plans to collect beautiful images of the BT-50, my trusty steed for the long and meandering drive out here, under the Milky Way with those dishes in the background.

Such photography requires flashes of light, of course, which would have seen me lynched by the astro mob for polluting their darkness. These people take their night activities extremely seriously.

+1

The very last purples quickly drain from the sky. The moon is in its brand new phase tonight and must be somewhere behind the horizon. It’s great for looking at stars but not for much else.

I turn the BT-50’s powerful, dark-dashing lights off and the blackness becomes absolute. Intense. All-encompassing.

Imagine you’re floating inside a giant opaque ball with nothing to light the interior. No matter who or what is in here with you, you can’t see a thing. Imagine also that the ball is full of pin pricks and it’s a sunny day outside. What would you see? That is what it felt like to be out there, under that magnificent pin-pricked blanket of black.

There’s no heat and my lips feel numbed, like I’ve just left the dentist. And because the air is still, my hearing develops a bat-like acuteness. I become hypersensitive to sound; the crunching of the grass underfoot, my breathing, the click of the camera. Every noise is bouncing off that perfectly spherical dome above me. And I’m alone.

The idea of camping out here tonight feels less and less appealing, even though I’ve set up the tent. The only visible source of light are those uncountable pinpricks. I escape into the safe enclosure of the BT-50’s cabin and shut the door. Call me a chicken, but I’m out of here.

I feel instantly secure in my Mazda life boat travelling down this dark highway. The odd vehicle approaches, beginning life like one of those pin pricks on the distant horizon. I pass roadside models of Neptune, Saturn and Jupiter and finally reach Coonabarabran late at night. There are lights here, and a smell of manure. I’m safe now. The interstellar darkness is behind me.

Within the safety of the motel I go for a quick stroll to the dark side. Yes, this motel has a dark side and campground specifically set aside for astrographers to observe and photograph the heavens from the comfort of the back yard. Standing in the cold blackness are a couple of lonely telescopes emitting faint beeps. I stay well away.

+1

In the early morning a shimmering white blanket of frost covers everything. The telescopes from last night are still standing, sparkling in the sunlight with steam raising from the top, like smoke from a chimney.

I find myself somewhat in awe of the equipment used by Prasan, one of the more hard-core night stalkers. His power pack is the size of two large car batteries and it drives the telescope mount or tracker (which costs as much as a small car), cools the camera sensor to minus 25 degrees and heats the dew shield enough to prevent any water settling on the lens itself. Hence the steaming telescope.

In addition it has hydrogen, oxygen and sulphur filters to isolate particular light frequencies emitted from the celestial bodies Prasan is focusing on.

After dark, he aims it at a particular galaxy or nebula or star cluster and goes to sleep. He takes photos of objects a billion light years away, probing deep space fields, taking five-minute exposures to create an image of something that might not even exist anymore, because the light reaching his incredible camera equipment was emitted light years ago. And in the morning he’s as excited as a kid at Christmas.

Yes, there’s a lot more to watching the stars than just looking up. And you need to be a particular kind of star fanatic to do it properly.

So how do you measure darkness? Well, if you’re fairly adept at identifying the heavens, you can use the Bortle scale, which relies mostly on your eyesight. Essentially, if you can see the M33 (not the freeway), globular clusters, and the gegenschein amongst some other things with your naked eye, the darkness is awesome; a Class 1 on the nine-level scale.

Alternatively, you can use a Sky Quality Meter (SQM). This is a small battery-powered device which measures the luminance of the night sky and quantifies the skyglow aspect of light pollution in magnitudes per square arcsecond.

The SQM goes up to 22 (perfectly black sky). Where I was last night, in what felt like freakish darkness, it apparently hovered around the 21.7 mark. And on a typical cloudless night Sydney is a depressing 14.

In 2004, the Warrumbungle Shire Council approved a plan to protect its dark night skies from deteriorating. Minimising light pollution by providing good lighting; the kind that is not pointed upwards, is of the right amount directed in the correct place and is not glary. Coonabarabran is the stargazing capital of Australia after all. There’s a Dark-Sky Movement here; a campaign to reduce light pollution. Even the old-school Warrumbungles Mountain Motel’s lighting is clearly designed with this is mind.

I ask the receptionist, Sally, if she gets many of them here, pointing my gaze at the four blokes still discussing the darkness of the sky. “Yes, and they’re all crazy”, she chuckles. “They usually come here in the winter months when the sky is clearer.”

Before leaving home, I fancied viewing the Milky Way from the base of The Breadknife, but that turned out to involve hiking, and I preferred the considerable motive force of my Mazda BT-50. The best view I found of the classic Warrumbungles rock formations (Crooked Mountains in the language of the Gamilaraay) is from the top of Mt Woorut, which is the perch for the Siding Springs Observatory and home to Australia’s largest optical telescope.

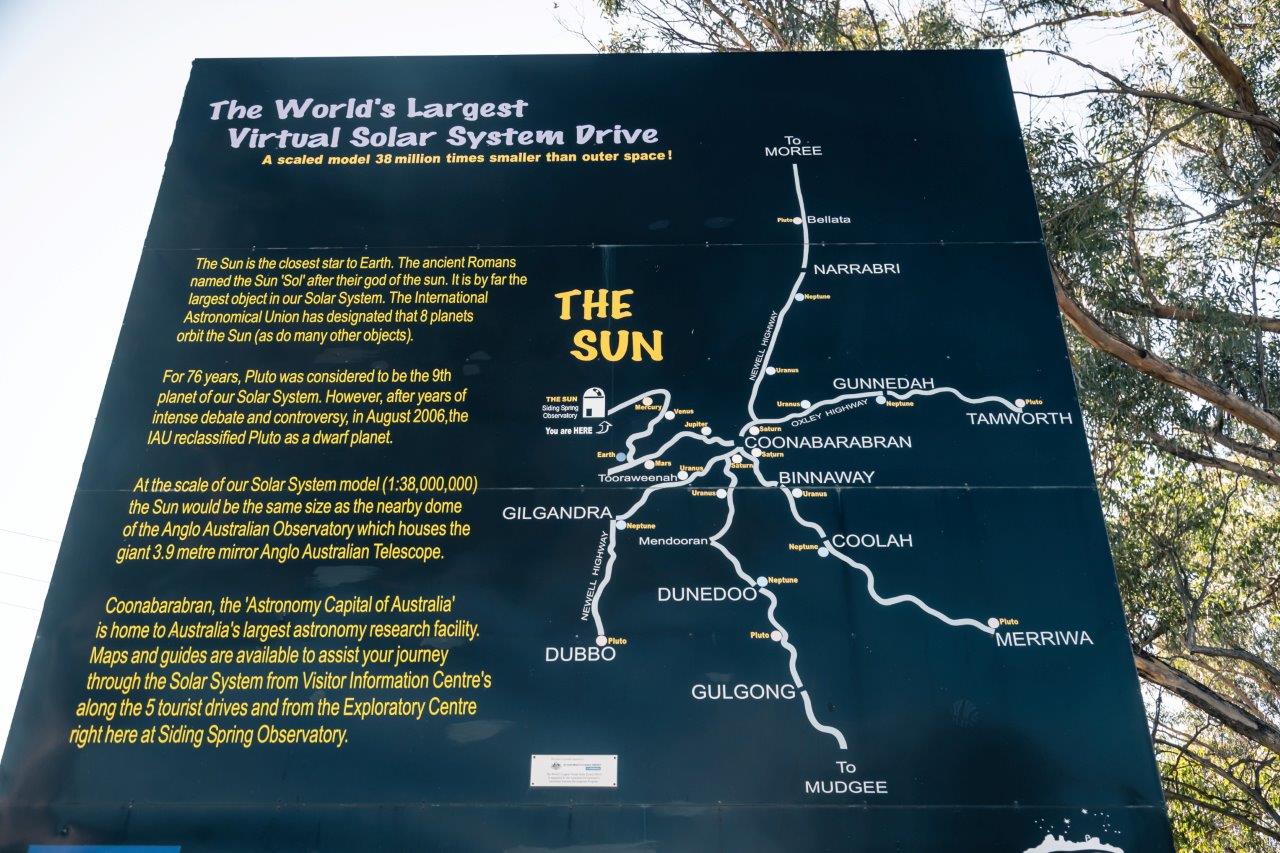

This very large telescope is also the centre of the world’s largest virtual solar system. At a scale of 38 million to one, the Earth is the size of a basketball and I’m the size of a microbe. The other planets are scattered along the web of roads culminating here. The outer reaches of this solar system go as far as Dubbo, Merriwa and Tamworth. Earth is only four kilometres down the twisty road leading to the highway.

Is there anybody out there looking back at us? Perhaps, but they could be long gone by now.

Even my most current perception of the sun is eight minutes old. And the darker the bit between us and those celestial objects, the further back in time we can see. That is why those astro nutters really don’t like having their darkness disrupted. I’ll know better next time.