Rotary dials back the years to the glory days of Mazdaspeed

Words by Iain Curry

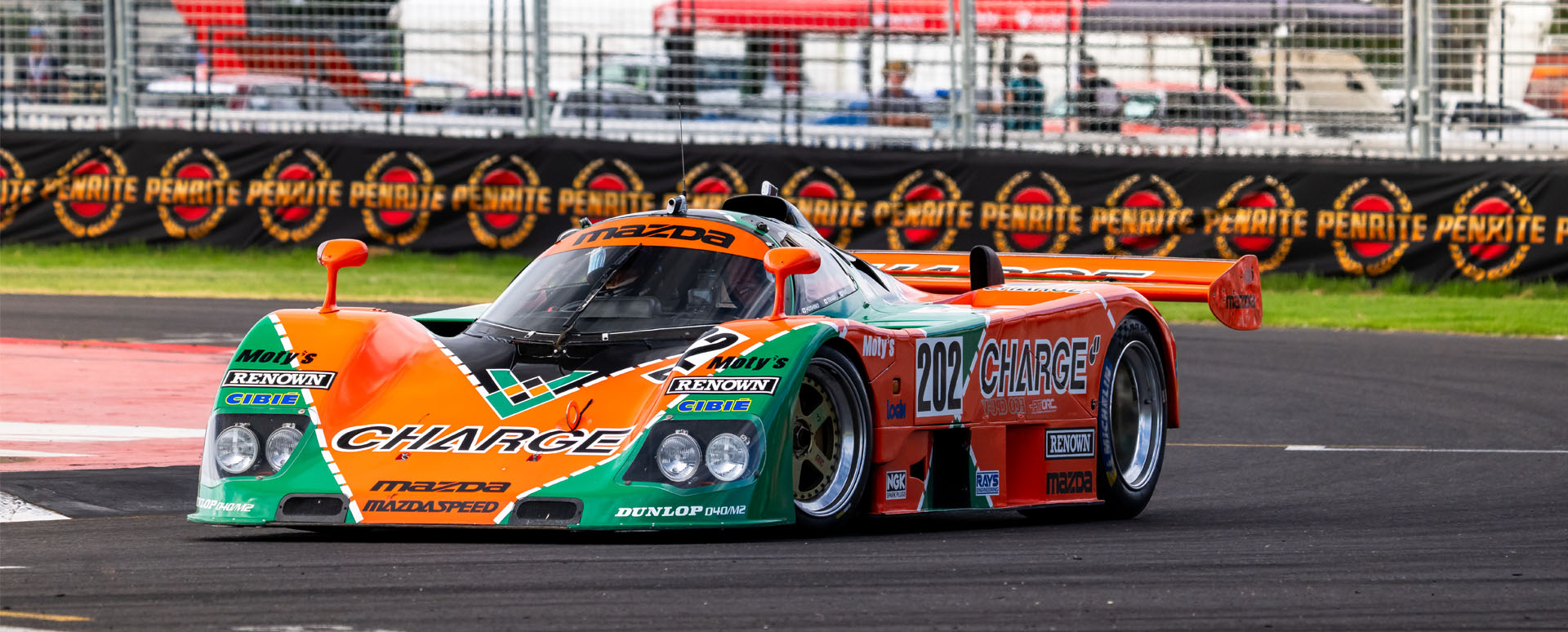

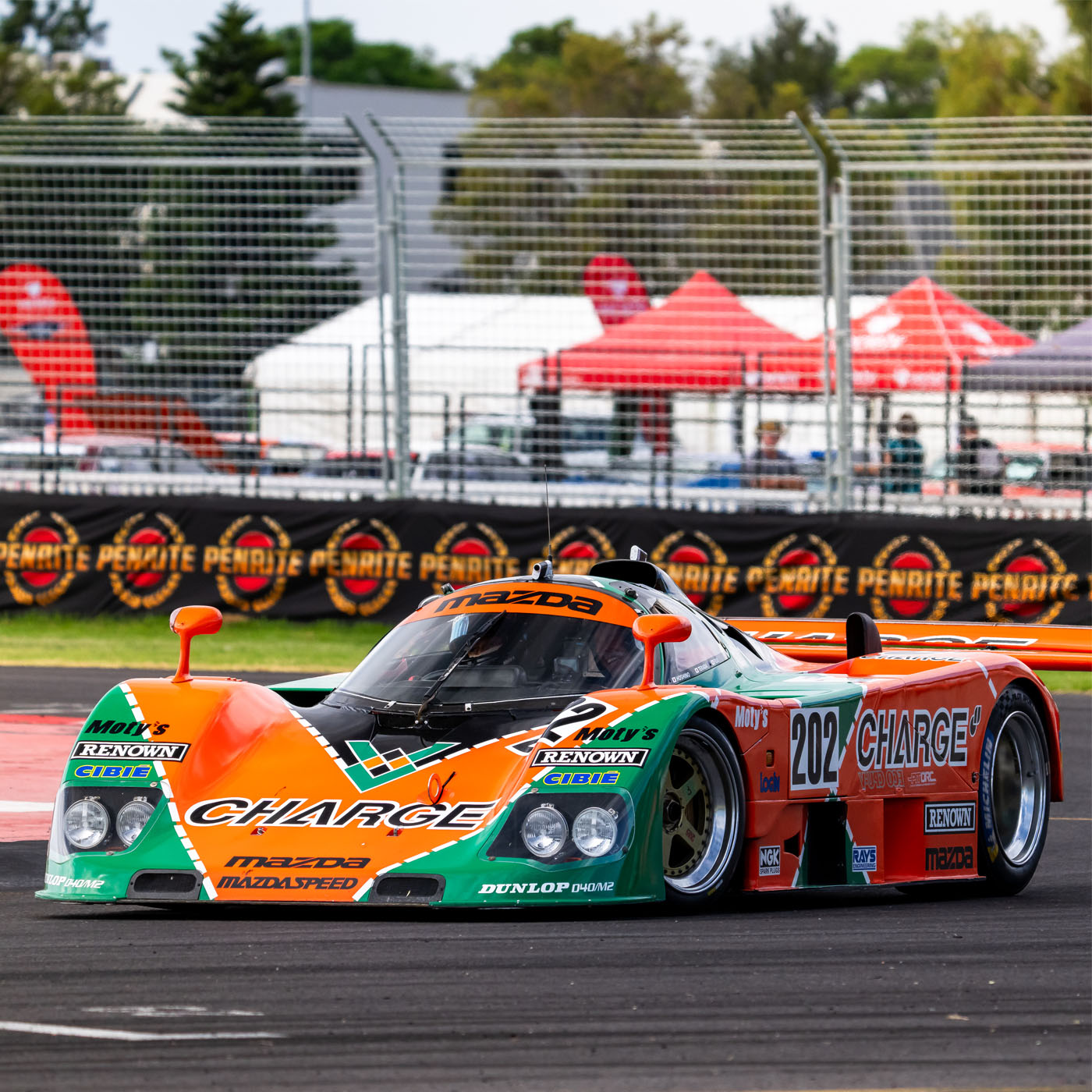

In a crowded Adelaide Motorsport Festival pitlane, Senji Hoshino’s face breaks into a mighty smile. His 1989 Mazda 767B’s quad-rotary engine has roared into life, he stops talking and - like everyone else here – simply listens to the raucous yet beautiful engine music playing from this bright orange and green race car.

The noise is all-consuming; the type that goes right through you. Remains with you. Hoshino-san recognises our conversation is on pause while Mazda’s famed 13J-M 2.6-litre rotary engine fills its lungs. It’s the very car that scored ninth place at the 1989 Le Mans 24 Hours, and is rightly recognised as possessing one of the most screamingly memorable engine sounds ever heard at the world’s most famous endurance race.

Hoshino-san’s 767B must be one of the best travelled and most eyeballed historic Le Mans cars. The owner/driver isn’t one to hide his legendary racer away, unlike many custodians of high-value cars. On the contrary, he believes it must be seen and used in its natural environment.

“It’s important for the fans to see the car, and hear its motor,” Hoshino-san explains through an interpreter. “I think of it as a world heritage piece, as Mazdas are the only rotaries (engines) to go to Le Mans and get results.

“Real racing machines were built for the track, and that’s where they belong.”

“Real racing machines were built for the track, and that’s where they belong.”

This belief has seen Hoshino-san invited to some of the world’s most prestigious heritage motorsport events, where he himself dons the race suit and drives his scene-stealing 767B.

There are the meets at Fuji and Suzuka in his native Japan; he’s tackled (and regrettably crashed at) the 2015 Goodwood Festival of Speed in England, and he’s thrilled crowds at Australia’s World Time Attack and Mad Mike’s Summer Bash in New Zealand.

Hoshino-san has had a long association with Mazda and, in particular, the brand’s famed rotary engines. He owns Garage Star Field workshop in Gunma Prefecture, north of Tokyo, and is a noted specialist and restorer of Mazda RX-7s and the gorgeous (and highly valuable) late-1960s Mazda Cosmo sports cars, one of the first production vehicles to use a two-rotor Wankel engine.

His rotary passion is obvious, but it’s a dramatic departure from an 82kW Cosmo to his fire-spitting Mazda prototype Le Mans car, one of very few in private ownership. Only three 767s were made in the period, and his is the second ‘767B’ chassis built by Mazdaspeed, Mazda’s in-house performance division of the time.

At the 1989 Le Mans 24 Hours, its sister car finished seventh overall; two places ahead of Hoshino-san’s car, itself two in front of the slightly less evolved 767 car introduced for the 1988 event. The cars filled the top three places in the IMSA GTP class in 1989.

This was an evocative, golden era of sportscar racing. At Le Mans that year, some cars hit more than 400km/h down the Mulsanne Straight. This 767B managed ‘only’ ’ 360km/h, but it was a race car yet to achieve its zenith. Two years later, Mazda’s evolved 787B became the first (and only) rotary-engined Le Mans winner, and Mazda was the first Japanese manufacturer to take overall victory in the gruelling French enduro. It was symbolic of the brand’s “never stop challenging” spirit.

Hoshino-san’s 767B is sleeker and arguably even prettier than the 1991 Le Mans-winning 787B. It sports the same eye-catching orange and green Renown/CHARGE livery, and in the flesh is a menacing quad-headlighted thing.

A carbon fibre monocoque racer, it’s surprisingly compact with the tiniest of overhangs past impossibly deep-dished Volk Racing rear wheels. It’s completely flat sided and sports a laughably huge rear wing, while the front bumper’s splitter is so low it cleans the pavement.

Hoshino-san bought his 767B some 25 years ago. “Yamanashi Mazda was part of Mazdaspeed, and they were using the car for demonstrations at the time,” he says. “I had the opportunity to buy it, and decided to take it.” It’s been a fruitful relationship ever since.

It’s the quad-rotary noise that most beguiled Hoshino-san. “It’s an amazing sound; a trumpet-like brass instrument,” he says. When describing it, he can’t help mimicking the dramatic pulses the engine makes, aping the high-pitched noises through the gears while he grips an imaginary steering wheel.

The engineering and advanced technology for the day also gets him animated. “Looking at this car carefully, all its bolts are made of titanium,” he explains. “I think it was the first car in history driven with titanium suspension springs, the first with a variable-length induction system, and then the 787B had the first carbon brakes. It was dedicated to world-first attempts; that’s the Mazda spirit.”

The quad-rotor 13J-M 2.6-litre engine’s reliability ensured all three 767s finished the arduous 1989 Le Mans 24 Hours. The rotary boasted about 630hp (470kW) without the aid of turbocharging, in a car weighing roughly 800kg. Hoshino-san says such reliability continues today. “Racing cars are highly temperamental machines, but in this car’s case, as soon as the switches are turned on, it fires straight away and the idling begins. It spins pretty smoothly, and I just tap the accelerator and it goes.” And boy, does it go. In Adelaide it must run with special mufflers to somewhat gag the rotary’s high-revving screams (otherwise local glaziers would have been flat out), but the gathered thousands still get a taste of one of motor sport’s most evocative high-pitched banshee-like wails.

The noise shakes your internal organs as Hoshino-san flies past along the urban street circuit. Without getting too caught up in nostalgia, the world is missing racing cars that sound this spectacular.

But it must be scary to drive, surely? There’s the performance, history and value to consider, plus Hoshino-san’s Goodwood accident that necessitated this 767B’s two-year restoration.

“Not at all,” he says, still with a sincere smile. “It is so very solid, it’s quite easy to drive and really good in a straight line. I think it would do about 340km/h, but I’ve only taken it up to 320km/h at Fuji Speedway.” Hoshino-san says this as if such velocity is as commonplace as brushing your teeth.

It's a blessing that such an enthusiast owns this perfectly proportioned slice of Mazda’s motorsport history. Hoshino-san seemingly takes as much joy demonstrating how special the 767B is as he does in piloting such a luminously vibrant Le Mans legend. And for this, we, and future generations, must be truly thankful.

As a final bit of advice for those who’ve never heard it, hop on to YouTube immediately. You can search for Mazda 767B, or simply type in ‘best ever sounding Le Mans cars.’ Popping up top of the charts will be a Mazda rotary wailer.

I promise it’s a sound that will stay with you.

Passenger ride in a Mazda 767B

A lovely quirk of the Le Mans 24 Hours is that all competing cars must, in theory, be two-seaters. In race trim there’s just the single seat, but for demonstrations a second chair – with zero padding, of course – can be fitted for a passenger thrill ride. And I do mean thrilling. This was my golden ticket, beside Hoshino-san, at the Adelaide Motorsport Festival.

Open the gullwing door and you must clamber over giant carbon fibre bodywork to contort yourself into the seat. It’s already cosy for one, but it’s a sardine-like wedge job for two. I can tell my driver’s unimpressed – I’m an 80kg six-footer and not a diminutive jockey-like co-driver.

It’s almost absurdly compact inside. There’s exposed carbon galore, just a mere post box of visibility through the front screen, and my helmeted head is at a seriously slanted angle on this priceless Le Mans car’s roof.

Regardless, I’m still able to appreciate how rudimentary everything feels compared to a modern race car. There are basic buttons, fuses, switches and a stack of analogue gauges on show, plus descriptive markings completed by hand in Wite-out. It’s wonderfully old school and a purist’s delight.

Hoshino-san switches everything to ‘Let’s Go Crazy’ mode, and the rotary engine springs into life. He blips the throttle and it’s utterly heavenly in a raw, mongrel way. The rev counter pulses, he selects first with the tiny white manual gear shifter in his right hand, lets the clutch out and we’re away.

Boom! Whack!

The torque builds rapidly but smoothly, the acceleration’s fantastic, and it’s sublime how mechanical, how pure, it all feels. And that quad rotary sound over my right shoulder… it’s just perfect.

This 767B changes direction like a startled mouse, but goodness it rides the bumps and kerbs hard. My awkward seat position doesn’t help, and my body takes a battering in our all too short five-minute blast. A three-hour stint at Le Mans, at full tilt? Those drivers were superhuman, and their bodies surely in agony after driving around the clock in a 24 Hour enduro.

But for the noise alone, it had to be worth it.