INNOVATE

HOW MAZDA WON 24 HOURS OF LE MANS

INNOVATE

HOW MAZDA WON 24 HOURS OF LE MANS

Thirty years ago, at 4pm on Sunday 23 June 1991, as Johnny Herbert flew down the Mulsanne Straight in his orange Mazda 787B, he received crackly news over the team radio. Herbert and his Mazdaspeed teammates – Mazda’s motorsport subsidiary – had won the brutal 24 Hours of Le Mans, endurance racing’s most famous event. It was an enormously popular and historic victory. No other rotary-powered car had ever won the race before, and Mazda was the first Japanese manufacturer to win the event. On the 30th anniversary of this famous victory, Zoom-Zoom looks back at how it came about, and what makes it so special.

Words Tommy Melville

The 787B’s success at the 1991 Le Mans race weekend was a decade in the making. In 1967, Mazdaspeed started life as an independent motor racing team launched by one of Tokyo’s largest Mazda dealerships, Mazda Auto Tokyo. Run by the indefatigable Takayoshi Ohashi, the team first entered Le Mans in 1974 and returned 13 times over the next 18 years. In 1983 Mazdaspeed became a subsidiary of Mazda Motor Corporation and, by the end of the 1980s, Takaharu Kobayakawa – Program Manager of the Mazda RX-7 – was responsible for Mazda’s motorsports activities; he and Ohashi would oversee the Le Mans initiative.

A regulation change meant Mazdaspeed knew the rotary engine that powered the car would be banned for the following season. It was now or never for the 787B. Elsewhere, Ohashi scored a small but critical victory in securing an amendment from FISA (the motorsport governing body at the time) allowing the 787B to run in its standard configuration, while the competition was required to add ballast as part of a new regulation. Finally, in the no. 55 car, the three hotshot F1 drivers – Johnny Herbert, Volker Weidler and Bertrand Gachot – gave Mazda hope that an overall win was possible.

The majority of the race was uneventful for the no. 55 787B. A strong start from Weidler saw him carve through the pack from 12th on the grid, and the car worked faultlessly through the night. The team saved time by performing only one brake change, instead of the planned two, and with three hours to go the no. 55 car was in second place – a testimony to its reliability, consistency and pace. Suddenly, the first-placed Mercedes-Benz, four laps ahead, suffered a fault and retired. The race was now Mazda’s to lose. For the next three hours the no. 55 stayed out front, and at 4pm it secured the first overall victory for a Japanese team at Le Mans. The team’s other race cars, the no. 18 and no. 56, prospered in the race too, finishing sixth and eighth respectively, a huge achievement. This event proved that Mazda could take on the European behemoths and beat them at their own game – and set a precedent for Mazda’s ability to do so again with its next-generation platforms.

“I was exhausted and dehydrated. It was only adrenaline that got me to the 24-hour mark.”

Johnny Herbert. The driver who finished first

Johnny Herbert belongs to an exclusive club of winners who never made their Le Mans victory podium. Rather than celebrating the trophy presentation with Mazdaspeed, he was unconscious at the track medical centre. The race had taken its toll. Over the weekend Herbert had struggled for sleep, and nerves had meant only instant noodles would both stay down and provide sustenance.

As the final few hours of the race progressed, Mazdaspeed Team Principal Takayoshi Ohashi and Consultant Team Manager Jacky Ickx radioed Herbert asking him to extend his driving stint to the end of the race. With victory so close, Ohashi was unwilling to risk the uncertainty of an extra pit stop and driver change. Herbert agreed but, exhausted and badly dehydrated, it was only adrenaline that got him past the 24-hour mark to confirm the win.

Herbert had been introduced to the Mazdaspeed team by Mazda driver David Kennedy in 1990. Recovering from injuries sustained in a near career-ending crash in 1988, he was highly regarded and had good Formula 1 (F1) experience. Herbert says the Mazda was “a lot easier than an F1 car” to drive, with downforce and g-force both significantly less aggressive. The cabin of the 787B was beautifully laid out and comfortable, and “the rotary engine was absolutely fantastic”. He remembers it as “silky smooth” and, crucially, bulletproof in terms of reliability. Herbert laughs when he recalls the gearbox as the “slowest in the world”, but it was designed for endurance over speed. While contemporary Le Mans teams can change a gearbox in less than two minutes during a pit stop, in 1991 the box had to last the full 24 hours.

Herbert insists the excellent 787B was a product of a team operating at the peak of its powers. Ohashi was “very shrewd and had a great sense of humour”. He had spent the previous decade enrolling some “brilliant engineering minds” and embraced a truly international recruitment policy, getting in the likes of British car designer Nigel Stroud and Belgian six-times Le Mans winner Ickx as an advisor and consultant team manager.

“Mazdaspeed was a very small team compared to the might of the competition, such as Mercedes-Benz and Jaguar,” says Herbert. But by June 1991 the team was “in a perfect position because it had been through a huge learning process” over the previous years. Seasoned drivers such as Pierre Dieudonné and Yojiro Terada brought experience to the Mazdaspeed driving roster and, despite being considered underdogs, there was no doubting the “hard-earned” nature of the victory that would come.

Thirty years after the event, Herbert’s memory of the race is unclouded. He remembers the camaraderie with his fellow drivers as they competed to get the most speed from the car while sticking to the prescribed fuel economy figures (1.9l/km of fuel). He remembers the “beautiful” scream of the 787B’s engine “as it ricocheted through the main grandstand and the paddock complex”, and through the night he remembers seeing trackside race fans asleep in their chairs and sleeping bags, lit up by the 787B’s exhaust flame as he downshifted through the Indianapolis corner.

Mostly, though, Herbert remembers the “huge smile” that spread across Ohashi’s face as their main competition, a Mercedes-Benz, overheated and retired, ceding the race lead to the no. 55 787B. As the 24-hour mark was reached and the victory confirmed, Herbert recalls the fans rushing onto the track to celebrate an “extremely popular” win. The no. 55 car became an icon and the fact that it took “27 years for another Japanese team to win Le Mans” is testament to the scale of Mazda’s achievement.

Grid position

12th – Mazda’s starting place on the track

Speed

205.333km/h – the average speed of the winning 787B

Weight

830kg – vehicle weight (170kg lighter than the standard race cars)

The 787B is fractionally longer and wider than a Mazda CX-30. It was the first car to win Le Mans with a carbon clutch and brakes, and its iconic paint scheme paid homage to Japanese clothing brand (and team sponsor) Renown.

Mazda’s four-rotor race engine first ran at Le Mans in 1988 and, after an unsuccessful 1989 campaign, driver Pierre Dieudonné said that it needed 100hp more to be competitive. A heavily revised engine with the required 700hp returned in 1990 and again in 1991, this time with an astonishing fuel-efficiency improvement.

The team entered three cars into the race: two 787Bs and one older spec 787. The job of the latter was to finish at all costs, saving Mazda’s blushes should reliability issues force the innovative 787B cars to retire. A spare car was also brought to France.

Takayoshi Ohashi was the team leader and beating heart of Mazdaspeed. He led the team from 1967 and his wit, leadership qualities and ability to deal with the political aspects of his role proved crucial in achieving victory.

The qualities each international team member brought to Mazda saw a slick operation and a camaraderie that has not been forgotten. Driver Pierre Dieudonné says he “relished the international spirit”.

“The no. 55 became an icon. A little bit of magic surrounds that car after the Le Mans win.”

Pierre Dieudonné, Mazdaspeed driver of the no. 56 787 in 1991

“The no. 55 became an icon. A little bit of magic surrounds that car after the Le Mans win.”

Pierre Dieudonné, Mazdaspeed driver of the no. 56 787 in 1991

Having won the 1981 Spa 24 Hours endurance race in an RX-7, Dieudonné was no stranger to success in a Mazda, but his memories of the 1991 Le Mans race are particularly special. During the race he recalls Johnny Herbert “suffering like hell” from his 1988 crash injuries, and watching bits of carbon work their way out of his feet between stints. “The team were not considered favourites,” he recalls, “[but Mazdaspeed] were technically strong and knew they had a chance”. He was also impressed by the Mazda team’s “relentless pursuit” of their ambitions and beliefs. Since 1991, Dieudonné has exclusively driven Mazdas. He currently runs a Mazda3, and his wife drives a CX-5.

“1991 was the perfect demonstration of Mazda’s determination to never give up.”

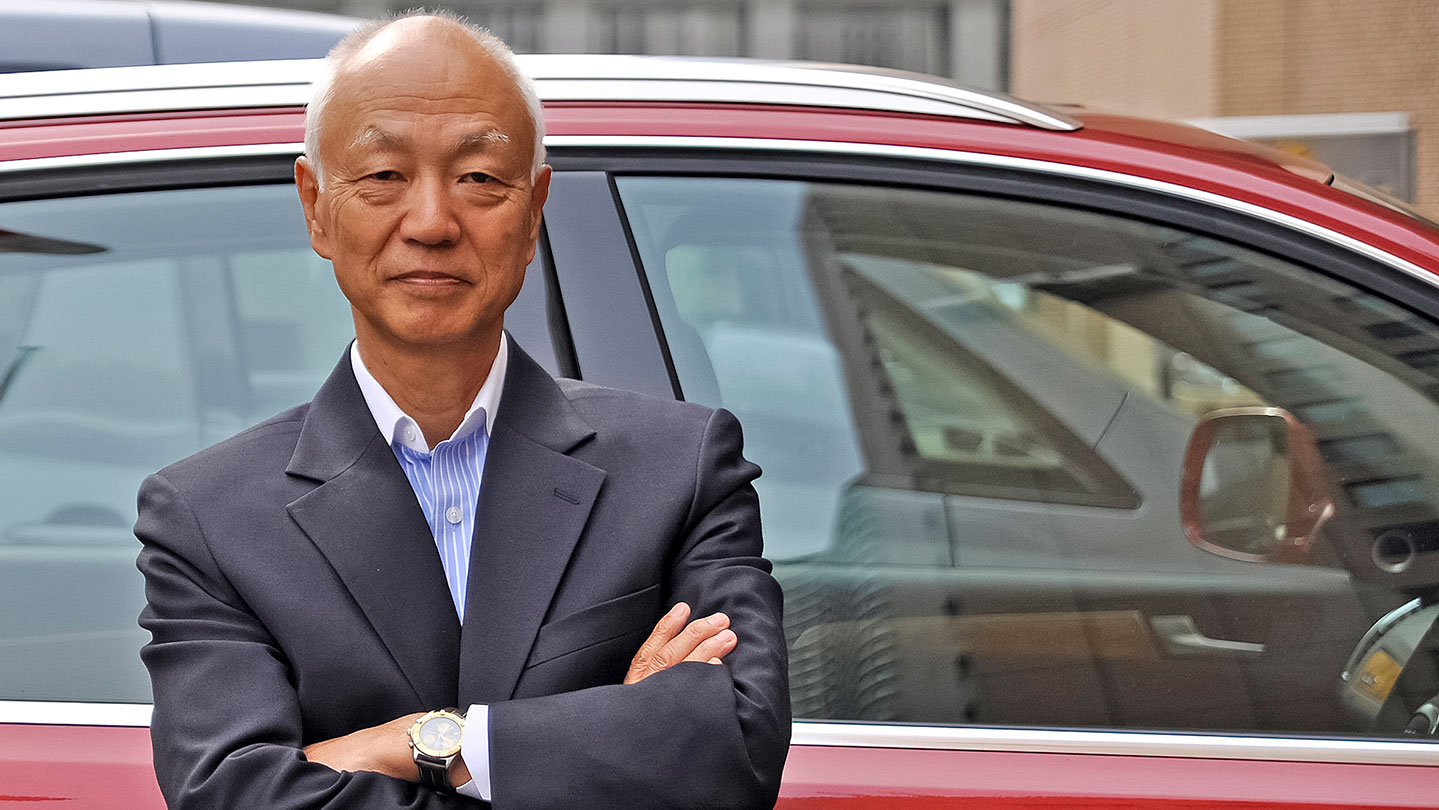

Takaharu Kobayakawa,

Mazda Motorsport Program Manager in 1991

“1991 was the perfect demonstration of Mazda’s determination to never give up.”

Takaharu Kobayakawa,

Mazda Motorsport Program Manager in 1991

Kobayakawa says that Pierre Dieudonné’s demand in 1989 for 100hp more from the rotary engine stunned the engineering department at Mazda. It was left to Yasuo Tatsutomi, Mazda’s inspirational General Manager of Product Planning and Development, to find the extra power, despite some of the team calling it “impossible” to achieve. Nevertheless, they rolled up their sleeves, cancelled holidays and worked every hour possible. Eventually over 1,000 improvements for the engine were proposed. Ultimately, 80 of these were implemented and featured in the 1991 787B engine. After the win, the engine was returned to Japan. Kobayakawa asked for it to be stripped for analysis and invited journalists to attend the process. The race engine was in such good condition, Mazda believes it could have run another 24-hour race.

About Mazda racing

Mazda burst onto the global motorsport scene with the audacious entry of two rotary-powered Cosmo Sport 110Ss into the 1968 Marathon de la Route. This gruelling 84-hour race at Nürburgring, Germany, was a huge challenge, yet one of the Cosmos nearly won, finally finishing fourth after experiencing a technical issue. With this race, Mazda had simultaneously announced its technical and racing prowess.

Since then, Mazda has seen much activity and success on the international motorsport stage, and that looks set to continue. Very few manufacturers do as much to promote and fund grassroots motorsport. The Mazda MX-5 sports car is one of the most widely raced vehicles in the world, and the marque’s specially prepared Global MX-5 Cup car variant has competed in numerous series.

In the U.S., Mazda is currently enjoying sustained success with the RT24-P endurance racing programme in the IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship.

The Global MX-5 Cup car in action.

The RT24-P at Sebring in 2020.

The Mazda Cosmo Sport 110S at the 1968 Marathon de la Route.

Find out more

The spirit of Le Mans lives on

Learn more about Mazda Motorsports